The scale, pace, and intensity of human activity on the planet demands radical departures from the status quo to remain within planetary boundaries and achieve sustainability. The steering arms of society including embedded financial, legal, political, and governance systems must be radically realigned and recognize the connectivity among social, ecological, and technological domains of urban systems to deliver more just, equitable, sustainable, and resilient futures. We present five key principles requiring fundamental cognitive, behavioral, and cultural shifts including rethinking growth, rethinking efficiency, rethinking the state, rethinking the commons, and rethinking justice needed together to radically transform neighborhoods, cities, and regions.

The scale, pace, and intensity of human activity on the planet 1 is driving global biodiversity and ecosystem decline 2 , fundamentally altering earth’s climate system 3 , and increasing social and economic global connectedness 4 in ways that threaten stability, resilience, and sustainability of local and regional human and ecological systems 5 . These patterns suggest we are living in what has been described as the Anthropocene Epoch 6 characterized by rapid and fundamental human-driven alterations of earth systems across the globe 7 . These major shifts to the stocks and flows of human life-support systems 8,9 challenge sustainability at any scale without fundamental and radical transformations in human activities and supporting financial, legal, political, and governance systems 10 .

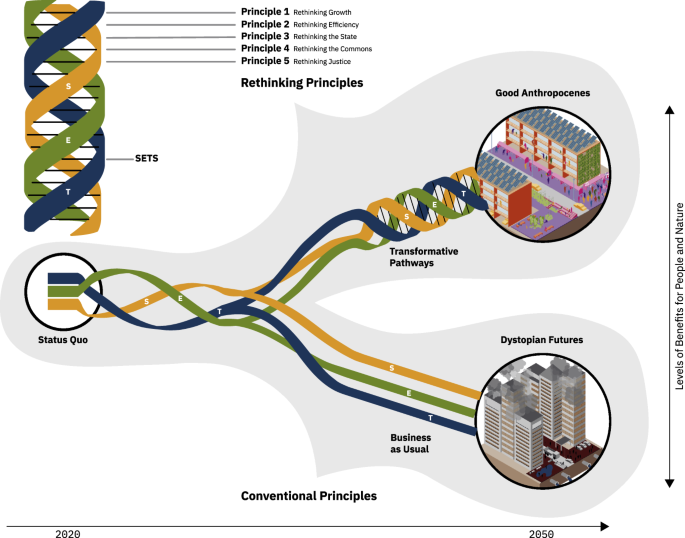

To shift the human enterprise toward a sustainable relationship with, and within, the earth system requires much more than small tweaks and incremental change 11 . Instead, it will require radical departures from the status quo 8,12,13,14,15,16 where the complex system of intertwined sustainability challenges 17 are confronted in order to shift multiple unsustainable trajectories toward ‘good’ Anthropocenes 18 where normative goals for sustainability are achieved 19 and political and economic power structures deliver the common good 20 . Radical change necessitates investments in knowledge, technology, institutions, and modes of business, as well as personal and socio-cultural behavior and meanings. Unlike existing approaches to transformation, radical change seeks to drive major shifts in understanding and actions across a broad range of diverse communities that can lead to shifts at both individual and organizational levels 21 . Tendency to focus on biophysical or economic quantification of the couplings between society and technology or society and ecological systems can overlook a critical element of radical thinking—the necessity to consider underlying social drivers such as capitalist competition and unequal power relations in ways that do not reproduce dominant growth and efficiency logics 22 . The radical changes required for transforming pathways toward ‘good’ Anthropocenes thus require more holistic, intertwined social–ecological–technological systems (SETS) understanding and approaches 23 .

We propose five key principles as necessary preconditions for societal transformation to achieve a good Anthropocene, one that is just, equitable, resilient, and sustainable. These principles include rethinking growth, rethinking efficiency, rethinking the state, rethinking the commons, and rethinking justice. We illustrate the potential to coordinate actions across five principles with the concept of connective tissues to ensure that dynamic linkages and feedbacks among interacting social, ecological, and technological–infrastructure system domains are considered and managed for driving transformation. In doing so, we attempt to reframe the dominant dystopian futures narrative to provide a conceptual framework and example case studies demonstrating how systems-level transformation can be initiated. We seek to open the door to new, more radical, and urgently needed systems-based policy, planning, design, and management approaches intrinsically based on the obligation to deliver positive, desirable futures.

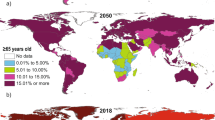

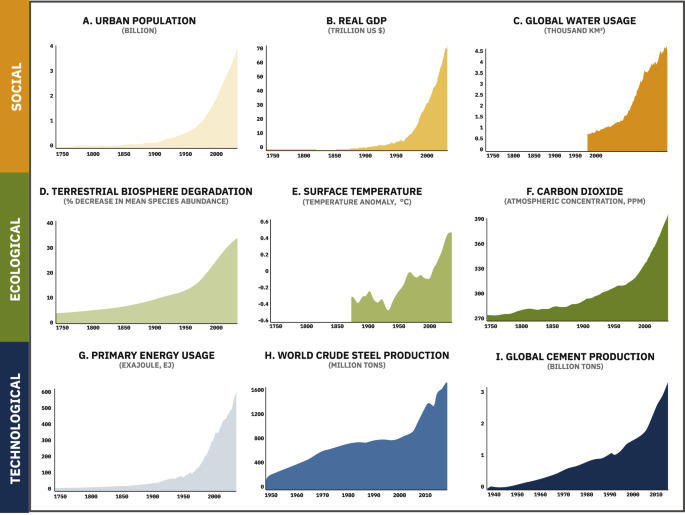

Globally, greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase, global ice has been rapidly disappearing, ocean heat content, ocean acidity, and sea-level rise are trending upward, all while human population, world GDP, air transport, and fossil fuel subsidies exponentially increase 5 . Moreover, average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900. More than 40% of amphibian species, almost 33% of corals and more than a third of all marine mammals are threatened by human activities 2 . At the same time, rapid urbanization has driven exponential consumptive demand for natural resources, energy, and built infrastructure, largely using outmoded 20th century design and construction techniques 24 (Fig. 1). This demand has generated interdependent and cascading risks, and threatens the resilience of human, ecological, and infrastructure systems, especially in urban areas where the majority of humans and infrastructure are concentrated 25,26,27,28,29 .

The future is therefore unsurprisingly dominated by dystopian narratives 30 that stem from business-as-usual projections of current trends in population, economic, and urban growth (Fig. 1). These narratives exist in prominent future scenarios from global bodies such as the IPCC, IPBES and other 31 economic scenarios, and which represent multiple future Anthropocene-related risks, such as from weather-related extreme events (e.g., drought, heat waves, coastal storms, and fires) 32 . Extreme events do not pose only future risks but are already impacting human and ecological communities 33 with complex local, regional, and global feedbacks that challenge human ability to innovatively manage the earth system at scale and alter current negative social and environmental trajectories toward more positive, desirable futures. While a return to past functionality or global climate has limited prospects 34,35 owing to its systemic complexity and our fundamental alteration of its dynamic stability, creating, owning, and acting upon positive visions that counter dystopian narratives is possible and critical to chart pathways, create motivation, and drive action in the present 16,17,30 . However, visions alone are insufficient. More radical transformative thinking is required that provides systemic leverage, actionable ideas, and supportive governance processes to develop pathways for how local, regional, and national innovations can be upscaled to drive global-scale sustainability transformations. Fundamental, and even radical transformations will require creative ways of connecting different types of actions and feedbacks across subsystems to promote positive tipping points 36 .

There is much debate on defining the Anthropocene. We follow Hamilton (2016) and consider the Anthropocene as the ‘recent rupture in Earth history arising from the impact of human activity on the earth system as a whole’ 37 . Anthropocene risks emerge from globally intertwined social, ecological, and technological drivers that exhibit cross-scale interactions from the local to the global 37 . As we improve ways to understand these complex interactions not only within and among systems, but also among resilience and sustainability initiatives, it is becoming clear that to alter earth system trajectories and create alternative pathways toward a better Anthropocene, we need more fundamental and radical transformations that can deliver systemic changes 19,23,28,38 . We define a ‘dystopian Anthropocene’ as one that broadly mirrors the present, where the current status quo is maintained into the future with human societies facing rampant inequality, unacceptable social and environmental injustice, economic models and development trajectories focused on growth, law used as a reactive tool to cement the status quo, and environmental ills from human-caused pollution, climate change, and ecosystem degradation unchanged or worse. In contrast, we define ‘good’ Anthropocenes as ones where these trajectories are reversed and the future is environmentally just, socially equitable, ecologically healthy, socially, ecologically, and technologically resilient and sustainable at all scales. To achieve the future we want will require radical changes in human cognition, behavior, and cultural norms but we argue, with others 39,40,41,42 that such change can begin by scaling up ‘seeds’ of positive futures that already exist across the globe. Scaling up such seeds, together with articulated pathways to the future that engage with diverse values, worldviews, knowledge systems, power structures (both political and financial), and scales, can promote transformations toward normative societal goals 43 . Such seeds of good Anthropocenes can include social movements, new technologies, economic tools, projects, organizations, or new ways of acting that support a prosperous and sustainable future, considering external drivers and cross-scale dynamics, as well as internal drivers of these interrelated systems. Transformation, however, requires more than scaling up current initiatives and innovations, and also a fundamental incorporation of systems approaches in order to be impactful and to have potential to scale at the level needed to meet global challenges facing not only human society, but non-human actors as well.

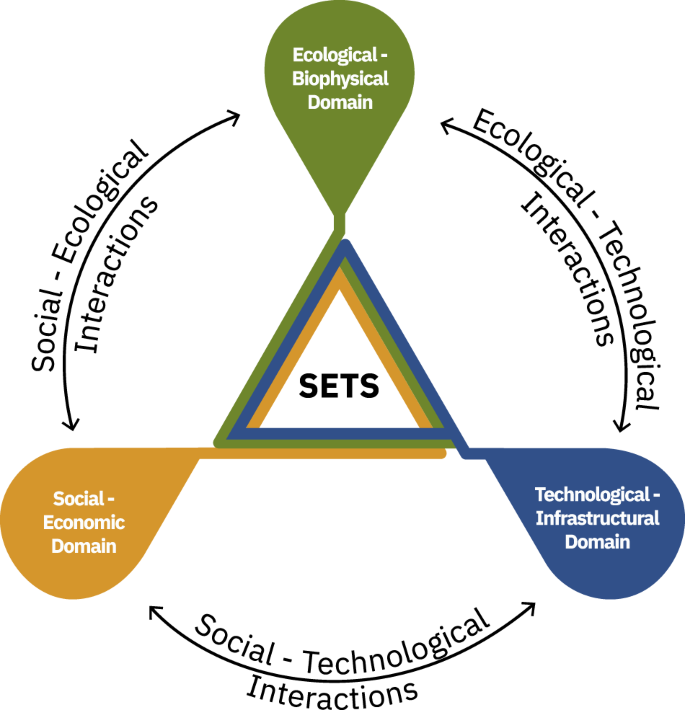

Social–ecological systems literature demonstrates that social and ecological systems are linked through feedback mechanisms, and display resilience and complexity 28,44,45 . Transitions in these literatures are commonly considered as co-evolution processes that require multiple changes in socio-ecological or socio-technical systems or configurations 42 . Modeling approaches have been developed to explain how different policy mixes influence social–ecological 18,46 or social–technical change 47 . However, existing approaches rarely consider the dynamic interrelationships across the full suite of SETS in a holistic manner to inform radical change. We utilize the SETS conceptual framework as a useful starting point for examining whether systems interactions are considered in transformation initiatives because this framework can help to understand the interlinkages or ‘couplings’ between elements of SETS 32,37,48,49,50 . The SETS conceptual framework (Fig. 2) complements recent scholarship in social–technical or social–ecological systems research 51,52 . SETS has been used in multiple cases and projects to enable examination of the interactions and interdependencies of human, environment, and technological–infrastructure interactions 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 and can be a way to analyze the potential of positive seeds of transformation to grow toward larger scale and more radical changes. The 2020 U.S. National Science Foundation’s call for Sustainable Regional Systems research argues for SETS as the conceptual foundation to anchor systems approaches that can deliver sustainability across urban and rural interlinked systems 50 . SETS thus aims to overcome the limitation of a purely socio-technological approach which tends to exclude ecological functions, or of social–ecological approaches which may overlook critical roles of technology and infrastructure, all of which are fundamental constituents and drivers of, e.g., urban system dynamics 58 . The SETS framework can therefore broaden the spectrum of the options available for intervention 48 and is a useful foundation to explore sustainability plans, actions, and initiatives, while identifying barriers to change within existing actions, governance frameworks, economic constraints, and value systems.

Here we use the SETS framework to examine the interdependencies across system domains within five key interrelated principles for rethinking human activity on the planet. We suggest that these five principles are among the preconditions for the radical transformations necessary to shift human–environment interactions toward planetary sustainability. Our use of a SETS framework focuses on three main system couplings (Fig. 3 and Table 1): (1) social–ecological (S-E) couplings refer to human–nature or social–ecological relationships, feedbacks, and interactions, such as how urban nature provides ecosystem services to support human health and wellbeing 59 or linkages between stewardship of urban green spaces and ecosystem change 19,60 , (2) social–technological (S-T) couplings refer to the ways in which technology and human social systems interact such as providing ability to communicate globally through social media 61 or the dependence on technological infrastructure to facilitate dense human living in cities; and (3) ecological–technological (E-T) couplings refer to the different ways in which climate and biophysical systems impact technology such as wild fires which cause power outages or rising temperatures driving increased energy use for cooling technology in buildings which in turn contributes to the urban heat island 62 . The SETS couplings are not limited to these examples, but rather provide a starting point for more holistic systems approaches in developing and scaling up sustainability initiatives at multiple scales.

We cannot solve complex challenges with simplistic approaches. We need more systemic experimentation and learning making it important that relevant SETS couplings be systematically identified, understood, and managed to address climate resilience opportunities or to transform interdependent systems to be more sustainable. We will also never be able to fully understand complex systems given constant change, dynamic feedbacks, and non-stationarity which creates uncertainties that can be reduced, but not eliminated. Thus, the SETS framework provides a middle ground for expanding systems thinking in multiple domains, while providing a starting point from examining linkages between S, E, and T domains in SETS couplings to build up ability to consider interactions, feedbacks, trade-offs, and synergies that exist within any subsystem, also, interacting across systems. We suggest that siloed efforts at transformation in only one S, E, or T domain without considering at minimum S-T, S-E, and E-T couplings and better S-E-T interactions, will ultimately fail precisely because they overlook the interdependent and complex nature of any SETS process, pattern, or dynamic in the Anthropocene, where humans and their technology dominate and undermine natural planetary processes 8,63,64 .

While SETS provides a framework for the application of a systems approach to defining options for managing Anthropocene risks, specific pathways and radical principles for realizing a good Anthropocene and operationalizing the SETS approaches are still needed, also, articulation and exploration of the connective tissues that can unite disparate transformation approaches across SETS. We propose five key rethinking principles based on an interdisciplinary literature foundation that recognizes the complexity and scale of the challenges facing humanity. We specifically consider the importance of core principles rethinking growth, rethinking efficiency, rethinking the state, rethinking the commons, and rethinking justice (Table 1) with reference to the S-E, S-T, and T-E couplings that need to be examined together in a specific intervention or initiative (Fig. 3). We provide examples of couplings for each principle, while also acknowledging that these examples are not entirely independent of other couplings, nor fully systems approaches, or even radical enough to achieve transformations at the scales needed. However, where case studies exemplify action on multiple principles, they are instructive of how we can begin to implement all rethinking principles and systems approaches for change. Examples are, however, ‘seeds’ that have potential to be replicated or scaled up, and more importantly, provide examples of how couplings and addressing core rethinking principles can help to set local urban SETS on more transformative pathways. Our framework and the five key principles are intended to reframe scholarly debate on sustainability transformations to a systems-oriented, adaptive, and relational perspective respecting the interlinkages across SETS. The core innovation of this perspective is not that any example or principle is in itself adequately novel or transformational, rather that bringing SETS perspectives and these five principles together can begin to provide the needed development of conceptual and methodological pathways for the radical changes we need to achieve a common and inclusive good for human and non-human species. We challenge planners, decision-makers, regulators, and governments at multiple scales to work together across system domains to develop more integrated strategies to achieve shared normative visions including the Sustainable Development Goals 65,66 . Civil society, active citizen groups, local government, local business, and the wider private sector replete with synergistic actions all have an important and obligatory role 66 in implementing the principles presented here. Processes of mosaic governance including governance sensitive to a diversity of forms of active citizenship, and cross-sectoral industry and government networks 67 cut across all principles with a view toward building shared ownership and transcending entrenched paradigms 38 while shifting toward good Anthropocenes.

Existing economies are GDP focused 11 and cost–benefit analysis driven with poor inclusion of externalities 68 , which promotes resource exploitation without full non-tradable cost/value inclusions 69 , and which are part of driving global crises 31 . Corporate sector interests in league with political entities are so powerful 10 that push back from transformative ideas is stymied because perpetual profit through an economic growth model is entrenched in policy, law, business, and global economies 22 . The principle of rethinking growth, we argue, involves, for example, the development and widespread adoption of new ecologically based business models, such as recognition of the co-benefits associated with investment in nature 31,70 and the multiple values of nature. This principle necessitates accounting for not only the social (non-dollar) value of natural capital, human capital, and produced capital 71 , but also more diverse values of nature grounded in ethics of care and reciprocity of human–nature relationships 72 . Rethinking growth means viewing degrowth 73,74,75,76 as an opportunity to slow exploitative economies based on shareholder capitalism, and co-create a value proposition that takes a broader stakeholder view incorporating the value–nature nexus accounting for long-term sustainability, social and ecological co-/dis-benefits, and that can drive global trends to deliver the SDGs 77,78 . While we acknowledge that ecological economics 79 and limits to growth theory 80 has been around since the 1970’s, these theories have not been applied at relevant scales (local to global) nor with the necessary governance framing to achieve the required radical societal transformations. We argue for rethinking growth particularly where economic utilization and adoption is viewed through the market–government collusive lens focussed on economic expansionary growth rather than planetary ecological limits and human well-being ensconced as the major driver for decision-making. Rethinking growth toward good Anthropocenes also requires incorporating alternate indicators of success other than GDP, profits, shareholder capitalism, and regulatory framing in order to counter the influence of a corporate oligarchy that has become increasingly global, politically influential, and financially unaccountable 10 . For example, a systemic shift from competitiveness scarcity and bottom line profit-driven, resource-depletive production processes, to ecological system limits, health, and wellbeing would be an important starting point 17,81 . Similarly, this principle means also creating a stronger community focus with shared decision-making such as collaborative abundances, participatory budgeting, promoting equity, recognition of altruistic outcomes, and improving opportunities for citizens 82 to become more effective collaborators and decision-makers 83 .

New approaches to rethinking growth in urbanization are provided by example of the Cheonggyecheon (which translates to ‘clear valley stream’) Restoration Project in Seoul, South Korea. This project is a large-scale urban greening effort in a densely populated city. The Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project complemented traditional valuation with considerations of social and ecological values over longer time spans by focusing on large-scale urban regeneration including removing a two-tier overpass and landscaping the river channel beneath it. The rejuvenated river system provides flood protection for up to a 200-year flood event, increased overall biodiversity by 639% (between 2003 and 2008), and reduced the urban heat island effect with temperatures along the stream 3.3–5.9 °C cooler than on a parallel road four to seven blocks away. This effort rejuvenated transportation and contributed to a 15.1% increase in bus ridership and 3.3% in subway ridership in Seoul and reduced small-particle air pollution by 35% 84 . Yet, we include this example not only because the urban greening represents a positive form of nature-based solutions 53,59,85 , but rather also because citizens were engaged in decision-making through an electoral process, providing active communication and consensus exchange between the government and its citizens 86 . S-E system couplings in this example are about enhancing human–nature value shifts, and broadening the valuation process to become more inclusive, rather than exclusive. The process considered fundamental human well-being, ecosystem functionality, and a recognition of the importance of building human–nature connections and long-term relationships.

S-T couplings in rethinking growth, beyond this case, can also refer to leapfrogging with disruptive technologies that include short to long-term impacts within a blended finance, microfinance, green finance, and crypto-finance regulated framing to help leap ahead of the barriers around implementing more equitable approaches for how investment is delivered to communities. Core to rethinking growth here is the need to breakdown fundamentals of the economic and financial institutions that see profit-shareholder value as the end goal at the expense of communities, nature, and long-term sustainable futures for the subsequent generations. S-T couplings in this principle go further to include bringing disruptive decentralized energy systems, mobility, and autonomous ground and air transportation technologies that move beyond incremental, to fundamental shifts in decentralization, and which localize ownership of essential services and jobs 87 . For example, the Community Power Agency in Australia uses local, people-powered clean energy projects to bring social, environmental, and economic benefits to rural and remote communities 88 .

Efficiency can be characterized in many ways, but in economics it is defined as Pareto efficiency, a desirable state, a resource allocation mechanism should achieve, in which no one can be made better off without making someone worse off 89 . Thus, efficiency is a welfare criterion for system design, be it a market or some other system. There is another, more intuitive and operational notion of efficiency, which concerns individual business profit maximization by means of increasing scale, specialization, and capital consolidation. Doubting that efficiency in the latter sense eventually leads to Pareto efficiency is deemed ‘anti-market bias’ 90 , ‘anti-profit beliefs’ 91 , or ‘emporiophobia’ 92 . However, this link is far from established, given the aggregate negative social and ecological consequences, such as environmental degradation, income inequality 93 , and food insecurity 94 . We argue that we must rethink efficiency and our default endorsement of the pursuit of business efficiency. We follow others to challenge the dominant efficiency discourse on whether and how it serves normative goals of society and, instead, argue for a view and action that is inclusive of the wider stakeholders that are impacted by business operations. We thus argue for a, seemingly, radical shifting away from consumption-based monetary growth toward one that values and makes decisions based on non-exceedance of critical environmental thresholds 31,95 . Efficiency then cannot be viewed in strictly economic resource terms but should be on the basis of ecological limits, environmental health, and human well-being rather than the lowest common denominator of, e.g., widgets per hour per dollar invested. We advocate for effective social and ecological beneficial use rather than efficiency.

Rethinking efficiency involves recognizing that the short-term and segmented pursuit of efficiency can not only harm society but also hinder transformative changes. Rethinking efficiency could illuminate new path-dependencies that can constrain production, transport, energy, and manufacturing transitions 96 or assist the diversity of stakeholders within these sectors to visualize the advantages of transitions, thereby helping to reframe the economic, political, regulatory, and technical operational framing in which industries, cities, and communities operate 97 . For example, urban farming could be reconsidered as a more holistic regenerative economic and ecological enterprise within open space governance, in which elements of social inclusion, employment welfare and livelihoods, and ecological resilience are considered in unison. Efficiency and productivity are not sole determinants of this regenerative system, rather the emphasis is on the development of a greener and more inclusive city that can deliver multiple benefits.

An urban example is Bybi, a social enterprise that endeavors to achieve such rethinking efficiency goals through bees and honey production in Copenhagen, Denmark (http://bybi.dk/om_bybi/). Bybi is responsible for more than 250 bee colonies across the city of Copenhagen. ByBi rents beehives to public, private, and social organizations in the city of Copenhagen, and in return, they participate in events, tours, and courses facilitated by Bybi. The beehives are housed around the city and Bybi processes and sells the honey and by-products produced by these rented beehives. However, we do not highlight Bybi because it is alone transforming the local SETS or working with all rethinking principles. Rather, we include it here because this initiative is not fundamentally about production of honey, but about creating a multifunctional system that has social and ecological benefits, and works across sectors including companies, social projects, local citizens, cultural life, and institutions. Though a small local initiative, Bybi represents a seed of good Anthropocenes that can be examined for opportunities to scale, both as a specific initiative and as a way to rethink societies’ focus on efficiency over inclusivity.

S-E couplings in this initiative emphasize the involvement of citizens in urban open space governance mediated by the central role insects and plants play to produce services and benefits. Stewardship in this case moves beyond the human as co-producer to encompass human and non-human interactions. Bybi actively employs unemployed people and those from vulnerable groups and provides training opportunities to those seeking new employment pathways. Low-income residents are provided a means of employment, which contributes to development of new skills and experiences necessary for future work. S-E couplings are showcased in how Bybi actively collaborates and engages with diverse stakeholders (residents, children, immigrants, unemployed, businesses, and government agencies) across the city to transport and distribute native and pollinator-friendly flower seeds for planting and pleasure. Here these actors collectively contribute to urban open space governance for people and insects and benefits are not focused on an efficiency model, but rather on shared human and non-human benefits.

To date, states have been unsuccessful in protecting the global ecological boundaries of the planet 95,98 . We argue that, despite calls for the dissolution of the state 10,99 , and recognition of this failure, states do have capacity and obligation to assume a more significant role in generating positive futures while acknowledging their limitations. States are neither all-powerful nor redundant in solving global environmental problems. By rethinking the state, we mean a conception of governance in which the state is not seen only as reacting to market failures with regulation but is an actor that can support emerging multi-scale governance initiatives at global and local levels, inspire markets and people, give societal direction with goals and obligations toward the earth system 100 , build capacity, mediate and resolve conflicts, and institutionalize best practices 101,102 . Therefore, transformative governance 103 is important for rethinking the state because it helps define issues of accountability, legitimacy, and transparency of decision-making and ultimately the political–market power relations that influence the implementation of new pathways 102,104 . In the 21st century, states must deal with a polycentric reality in which societal power is divided among a variety of public and private actors at all levels of governance ranging from local to global 105 working toward developing institutional flexibility, improved adaptive capacity, and ecosystem reflexivity via adaptive policies 106 . By rethinking the state, we seek to avoid the dual trap of negative externalities and societal instability associated with relying on markets alone, and the utopian picture in which powerful states have the political mandate and the power to force markets and people into submission with regulation 107 . By rethinking the state and harnessing its positive powers for good Anthropocenes, we also mean addressing how negative market externalities can be reduced and public participation and self-governance strengthened without losing the immense innovative potential that markets and people hold.

Despite compelling arguments illustrating structural barriers for states pushing transformative goals with significant economic and social trade-offs 95,98 , there are also examples of states pushing transformative change despite such pushback. For example, the European Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC) as an example of rethinking the state seeks to improve—and stop the deterioration of—the ecological condition of fresh surface and groundwaters as well as coastal waters within the European Union (EU). The legal obligations stemming from the directive for the EU member states, companies, and citizens are directly linked to ecological system boundaries and latest scientific knowledge. Similarly, impact-based regulatory strategies have been developed at the EU level in other sectors, most notably in climate change mitigation 108 and managing declining biodiversity 109 . Although such regulatory strategies can exemplify an advanced form of an environmental state rather than a green state respecting global ecological boundaries 98 , it is notable that for instance in the water context, the Water Framework Directive is gaining transformative impact with ripple effects across most natural resource-intensive sectors with impact on water quality. For example, in 2019, the Supreme Administrative Court of Finland (SACF) declined an environmental permit from an estimated 1.4 billion euro industrial bioeconomy investment due to declining ecological water quality, despite major political controversy over the matter. The case exemplifies that legally binding goals can have a strong impact for sustainability, social and economic trade-offs notwithstanding. In this context, it is important to underscore that states are complex institutions in and by themselves with multiple levels, sectors, and actors 110 , which have potential to facilitate overcoming structural barriers of transformation.

While the directive establishes a top-down planning and management structure for the EU waters, it also seeks to facilitate public and private collaboration, innovation, and tailored solutions for reaching the goals 111,112 . Here, the EU sets the overall, legally binding goals which are then implemented in state-level legislation, and ideally adapted to regional and local conditions in a collaborative process. While the role of such top-down instruments is controversial in societal transformations, research suggests that law can function as a crucial trigger for shifting governance onto a more sustainable pathway 113,114 . These shifts are far from linear and no top-down instrument—even one requiring contextualization and local-level involvement—can be expected to offer silver bullets in transforming governance. All such shifts are likely hindered by path dependencies in the governance cultures of institutions tasked with implementing change 111,112 . Top-down instruments can, however, plant the seeds toward shared visions of desirable transformations. In so doing, they perform a crucial societal task despite often slow and uneven progress, potentially providing a transformational change toward a steady-state economy that serves to deprioritize growth and market exploitation as state policy 95 .

By considering S-E couplings in this case it is clear that ecological problems related to overuse and pollution of waters have historical roots and strong societal path-dependencies. Achieving good ecological status of waters cannot be solved in isolation of the social context that is producing them. Legitimate and effective governance solutions need buy-in from market and local actors, and also government-imposed direction as well as conflict mediation and resolution such as court proceedings. S-T couplings would also recognize the societal demand for, or the market imposition of, AI, IoT, and other smart solutions that are pushing rapid development in information technology. On a global level, servers and other information technology infrastructures are a major consumer of water. Water is needed to produce energy (either directly through hydropower, or indirectly through cooling nuclear, coal, or other operations), or to cool down servers. Competition over scarce resources escalates demand for conflict mediation and resolution related to water, and also demand for global planning and steering on the most ecologically suitable locations for running servers and other IT hubs sustainably.

Considering E-T couplings underlines the importance of new technological breakthroughs in monitoring of water status, water purification, water efficiency, flood management, and energy production that can help alleviate the ecological stress caused by human activity and help accumulate revenue from water. These technological breakthroughs alone are unlikely, however, to solve the overuse and pollution of waters in the long-term 115,116 . New technology creates room for new development which in turn creates new water-related challenges (e.g., a shift from water-intensive production of cotton to oil-based acrylic textiles causes release of vast quantities of microplastics to waters 117 ). In order to foster a sustainable relationship between humans and water, a rethinking of the human–environment interface is required. States may need to impose limits for societally detrimental development with regulation, but the societal pathways toward this end should not be limited. Market and local actors need regulatory direction, and also room to innovate, adapt, and self-govern.

The commons may concern ecological commons such as nature-based solutions 118 , cultural commons such as music and arts 119 , knowledge commons regarding social practices around knowledge 120 , co-ownership and cooperatives 121 , and also digital and hybrid commons referring to digital domains such as sharing platforms, bartering sites, cryptocurrencies, and open-source data platforms 122 . Rethinking the commons refers to changes in the way we understand, govern, and use physical, cultural, and intellectual commons to ensure their long-term availability to all members of a society.

For example, the recent surge in cities investing in nature-based solutions 27,59 showcase the pathways needed to rethink the natural resources and open space commons beyond the creation of green areas. Emphasis is placed on building trust in local government and the experimentation process, learning from social innovation, improved access, co-creation, and co-implementation 28,123 . The commons may serve as powerful opponents to the dominating capitalistic systems, which often counteract quests for more transformative changes toward good Anthropocene futures 17,18 . In this way, a commons-oriented approach promotes citizen-led innovation and participation 122 .

Rethinking the commons includes the generation and qualitative improvement of new and existing public urban spaces. Whereas urban development often is focused on private development and the facilitation of car transportation, seeds of good Anthropocenes in urban development illustrates rethinking of urban spaces and an orientation toward more green, just, and healthy neighborhoods 124 , also termed urban recalibration 125 . For example, the City of Barcelona has installed a series of superblocks, a grid of roads with interiors closed to motorized vehicles and above ground parking and gives preference to pedestrian traffic in the public space, combined with recreational areas, meeting places, and more greenery 126 . The interior of each superblock can be used by residential traffic, services, emergency vehicles, and loading/unloading vehicles under special circumstances 127 .

E-T couplings in the Barcelona case could include making digital environmental data available for common use as it is increasingly provided from sensors, satellites, social media, and crowdsourcing. Equitable access to this data could provide both better information about challenges, and also enhanced capacities for co-creating innovative solution strategies sharing not only decision-making, but also the data and diverse forms of knowledge needed for decisions that can transform multiple domains of local SETS. Access to data and innovative use of technology, like other solutions, must be considered in contrast to social and ecological solutions and co-developed with residents to ensure that such urban development innovations are not co-opted by high private investments that prioritize economic returns relating to the establishment of sensor systems, and drive social abuses 128 .

S-T couplings here involve re-emphasizing the role of public infrastructure as shared spaces, resources, and transportation services that can be provided for common use and more equitably. The digital commons can provide new possibilities for citizens to engage in the planning, design, and management of open spaces. In Barcelona, citizen science data is supplemented by data collected using smart sensors. Sensors are integrated into parking and transportation, to trash collection, air quality, and parkland irrigation. The data is fed into the ‘Barcelona Digital City Platform’ 129 which is available to citizens, private companies, and other interested parties, but the city and its people retain ultimate ownership, and decide what constitutes proper access and privacy 130 . Of course, tensions remain and need to be further examined, such as between ideals of the post-capitalism sharing economy or community economy practices, and the way in which the platform economy has developed with exploitative practices 128 .

Rethinking justice in the Anthropocene is concerned with transforming the social, climate, economic, and political systems in ways that address disproportionate impacts and injustices. For example, climate change-driven extreme events are increasingly shown to have disproportionate impacts on the poor and marginalized, and there is concern regarding ethical issues around the unevenly allocated benefits of industrialization 131 . When considering risks from climate change impacts, this includes managing procedural, recognitional, and distributional justice issues associated with asymmetrical impact and skewed vulnerabilities 131,132 . Rethinking justice means also not only taking environmental and social justice movements further, but also advancing ecological justice, which evokes notions of reciprocity and care for humans and non-human entities, and so requires the exploration of new regulations and procedures for recognizing and managing for the rights of the non-human 132,133 .

Fundamentally, rethinking justice means examining how, e.g., climate change impacts and climate resilience actions will affect the relationships between people and place 127 , the range of knowledge and experiences of environmental change that impact everyday life for individuals and communities 133 , as well as considering how these knowledges are integrated into the governance and management of the city 134 . Rethinking justice is also about building adaptive capacity to manage sudden, violent, and catastrophic weather events or slow, long-term destruction such as drought and wildfire through new forms of adaptive and more diverse representational governance 135 .

For example, new forms of digital engagement and civic participation provide opportunities for recognizing the needs and rights of a diversity of interest groups 66 . In Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, East Africa’s fastest growing city, university students and local residents have been engaged in a community-based mapping project called Ramani Huria (http://ramanihuria.org/) to create accurate maps of the most flood-prone areas of the city. Models predicting current and future flood risk are based on the data collected from the participatory mapping sessions digitized into OpenStreetMap and enhanced with GIS analysis and aerial photos from drones. This project drew on the knowledge of residents in an area of Dar es Salaam housing approximately 1.5 million people, the majority living in informal settlements and highlighted how environmental justice is fundamental to understanding climate risks. Results from this citizen science-based risk assessment processes revealed that while the majority of residents in flood-prone districts understand extreme flood risks, they are unable to move due to financial constraints, commuting time, or do not desire to move due to community and family ties.

Examining the S-E couplings in this case helps address elements of distributional and recognition justice in terms of who benefits from natural resources, and where. In a good Anthropocene, all living beings should have a right to access, occupy, and use urban space and exercise democratic control over the current and future development of the city. In Ramani Huria, residents’ place-based knowledge has the potential to strengthen their rights and capability to live in their homes in the future. Residents can share information about flooding patterns and channels, risk of flooding, and flooding occurrence using participatory mapping tools, supporting climate resilience planning and empowering residents to better understand the issues, potential solutions, and methods of communicating climate risks to local authorities 136 .

S-T couplings in Ramani Huria suggest that participatory approaches to digital geospatial technologies provide novel opportunities to investigate elements of procedural and distributional justice. Local knowledge can complement the data availability gap needed to model and predict future risk. This data is a useful source for adaptive community and multi-level governance decision-making about resilience to support residents’ ability to stay in their homes. Next steps could support E-T couplings including multi-species monitoring and decision-making, giving voice and rights to local waterways.

In 2020, society continues to deal with existential challenges generated by the social, political, and economic norms projected largely from the 20th century setting us on a potential path to deliver a dystopian future in which human society and ecological systems collapse. On the current path we can expect to confront the planetary limits of natural resources, not only to provide basic life-support services necessary for human survival, but also to adsorb the by-products generated by food and energy production, material transformations, with concomitant pollution of water, land, and air resources 63,74 . Indeed, considering climate change alone, even if all nations meet their carbon emission reduction targets under the Paris Agreement, remaining emissions put the world on climate change trajectory that may lead to a 3 °C or warmer world with dramatic social, ecological, and technological consequences few have been willing to contemplate.

We suggest that by re-evaluating and rethinking through a SETS conceptual approach some of the most important societal drivers of global environmental and social change, we can build pathways that allow for the radical transformations needed to move the human dominated earth system toward a shared urban future we all want. Dominant, conventional principles that need rethinking (among likely others) include: (1) growth: the economic growth paradigm (exemplified by GDP), with capitalism as the vehicle that is maintained as necessary for employment, upward mobility, and technical advance 74,75,137,138 ; (2) efficiency: the efficiency of market systems and the assumption that businesses can efficiently and fully provide the goods and jobs necessary for a prosperous life within ecological limts 75 ; (3) the state: the neoliberal narrative about the incompetence and inefficiency of the state and the assumption that the state should play a reactive rather than proactive role in environmental governance 22,11 ; (4) the commons: that the commons deserve to be privatized or regulated by the state to avoid the potential for shared resources to be overexploited by individual users 105,107 and social–ecological systems frameworks, which provide for the regulation of the commons but often overlook how to facilitate and remove barriers to adaptive governance and self-organization to maintain resources 101,105,139 ; and (5) justice: that humans and non-human species have unequal or even no rights to a clean and healthy environment 139 .

Consideration of the five principles in isolation of one another will not drive transformations toward urban sustainability. Indeed, any single principle in itself is not necessarily novel, and has been well described in diverse literatures. The contribution we offer is to bring rethinking principles together as core needs that together must all be addressed to achieve the kinds of radical changes needed for fundamental societal transformations. The connections between the principles are foundational to any system change to ensure the integrity of S-T, S-E, and E-S couplings during the implementation of disruptive innovations and to avoid siloing of innovative solutions. Intermediaries, also termed intermediary actors 139 or knowledge brokers 140 , support accelerating transitions toward more sustainable pathways by removing or reducing blockages, pre-empting unintended consequences of change dynamics, and thus connecting different components and domains of the system 141 in what we refer to as fostering the ‘connective tissues’ between SETS strands.

Strong connective tissues including strong causal interactions between system components are also necessary for positive tipping points in the form of ‘domino dynamics’ or a ‘tipping cascade’ where one system causes the tipping of another, or to ensure deliberate interventions into a given principle can take the whole system down an alternative path 35 . Strong tissues can also provide resilience to negative stressors. Following Elmqvist et al. (2019) 28 , we propose that these tissues enable a system to maintain function in the eve and aftermath of a disturbance.

Recent examples of these tissues include the sudden shift to virtual care in Australia in 2020. While in part driven by COVID-19, this shift also reflects a connection between a rethinking of efficiency, the state, the commons, and justice. On March 13, 2020 the Australian Government added new telehealth items to the Medicare Benefits Schedule enabling health-care providers to offer both telephone and video consultations. This scheme was extended to all Australian patients on March 30. Before then, Australians inside major cities did not have access to these services. With a system change, the total number of consultations rose significantly, from 10.8 million in February to 12.9 million in April, 2020. The telehealth switch also prompted an overnight shift in the way health care is delivered in Australia 142 . The government made sudden changes to legislation and regulation, and finance and support programs to enable online treatment (e.g., rethinking the state). Justice principles were also re-thought concurrently with the provision of new apps and technologies for health delivery. To avoid many of the issues associated with patient isolation, AUS$10 million was assigned to the existing community visitors’ scheme and to train volunteer visitors to combat social isolation caused by COVID-19 (e.g., rethinking justice). New apps were developed to enable volunteer visitors to connect with older people both online and by phone 143 . We may expect trade-offs to emerge associated with the rapid delivery of these online support systems, including the increased inequality due to people’s different abilities to afford smartphones or computers, or difficulties to consult over the phone. Time will tell whether this initiative is transformative over the longer term, but it serves as an example that shifts can happen across rethinking principles, and even quickly 144,145,146 .

We provide the example to illustrate how strong connective tissues between the principles are needed, and that all five rethinking principles will need to be operationalized together for fundamental SETS transformations. The SETS framework, combined with connections across the rethinking principles, can help to identify potential trade-offs and ways to address them while aiming for transformative change. In this way, the five rethinking principles ‘pull’ the evolution of the coupled SETS strands toward more transformative pathways creating the conditions for good Anthropocene futures, while the connective tissue between the SETS strands can enable a close coupling and a coordinated realignment of societal activities, goals, and opportunities (Fig. 3).

We assert that society needs to not only rethink the conventional principles and their underlying drivers that define the status quo and underpin the current trajectories that put us on pathways toward dystopian Anthropocene futures, but also the connections among them to ensure transformative change. In our SETS framing, good Anthropocenes are ones where the steering arms of society including embedded financial, market, legal, political, and governance systems are realigned and coordinated through connective tissues so as to support multi-functionality. The tissues enable connectivity among social, ecological, and technological domains of SETS. We propose that radical rethinking along the five fundamental principles, combined with governance systems to strengthen the connective tissues among them, are paramount to enabling critical transformations toward good Anthropocenes. We have provided some examples of early ‘seeds’ of those rethinking principles in action that provide a starting point, though these are neither perfect examples nor address all principles or all SETS couplings (explore more seeds further at goodanthropocenes.net). There is still considerable need for advancing sustainability research for transformation. We suggest five key actions for research scientists to effectively contribute to this advancement.

We encourage further studies to identify similar SETS couplings, to put forward additional principles that must be re-thought, and to support their mainstreaming together to help initiate and foster the radical transformations toward a good Anthropocene urgently needed.